[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

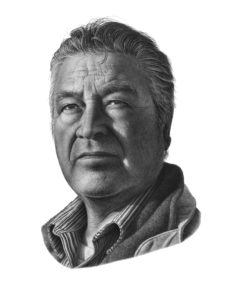

Growing up, William Dysart recalls challenging times where his family, like many others, had to choose between attending school or receiving an education out on the trap lines and lake, fishing and hunting. Schooling in the community was not up to standard and did not prepare students for the realities of life in South Indian Lake. They were unable to teach students how to hunt and trap, and how to negotiate with buyers.

Growing up, William Dysart recalls challenging times where his family, like many others, had to choose between attending school or receiving an education out on the trap lines and lake, fishing and hunting. Schooling in the community was not up to standard and did not prepare students for the realities of life in South Indian Lake. They were unable to teach students how to hunt and trap, and how to negotiate with buyers.

When spring arrived, many families moved to their trap lines and lived at their fish camp during summer, where buyers would often fly in and purchase fish from local fishermen, exporting them on planes to the nearest rail line at Lynn lake. William recalls spending much time with his family learning how to fish and trap, “We didn’t need much equipment to make ends meet. The lake had much to provide, it was enough for people, they had what they needed from the land.”

When hydro came in the early 70’s, people were able to get other jobs, like working for the contractors building the Churchill River Diversion (CRD). The CRD displaced the entire community, moving them across the channel. They had no choice. Manitoba Hydro was going to take over the water and reverse the flow. People weren’t given a choice of where they would live.

Once construction settled down and only the odd employee was left in the community, the fishing and trapping industries went downhill. “I don’t think nobody could put a number on it. They kept telling us their studies said there’d be a bigger lake and more fish. We kept waiting for the fish to come, and it didn’t happen.” Compensation was provided, but after it was used up on trying to save their fisheries, that was it. Fish populations were affected, erosion and water fluctuation impacted spawning grounds and there was a rapid decline in the whitefish populations of South Indian Lake.

Like many others, William tried to adapt to the changes. He relocated his fishing industry, bought a plane, and flew his own product out to buyers. But this was unsustainable. All of his money went towards his equipment and he could barely get by. William realized that there was no use continuing on this way. “They got what they needed, the water. The bank running through our town was Hydro.”

William says his main concern is for the younger generation. “Our young kids don’t know what they lost, the local town and school is all that’s left for them.” To make a life for themselves, they must move away from home, away from their families and traditional territory. They only see the damage caused by hydro development, they don’t see the value and opportunities their communities once had. William hopes that we can educate the youth on the past, and secure a better future for them. “I’m hoping someday they [Manitoba Hydro] could come and sit down and talk with us about it. There’s got to be a solution. People aren’t gonna move away from here. Too late for that.”

Northern Flood Agreement. (1977).

Know History Inc. (2016). Hydroelectric Development in Northern Manitoba. A History of the Development of the Churchill, Burntwood and Nelson Rivers, 1960 – 2015. Presented to the Clean Environment Commission.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies.

Manage your cookie preferences below:

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.